- 1502 Alabama St.

- Houston, TX 77004

- USA

- 713-529-6900

- station.museum.houston.tx@gmail.com

- Closed Monday & Tuesday

- Open Wednesday - Sunday, 12PM - 5PM

- Free Admission!

Aimé Mpane, “A Bomb with a Time-Delay”, 2007, broken glass, figure made of stems of matches on plastic carpet, variable dimension

The day ends

Spreading millennial histories

Out over the earth so that

He who reads shadows

may see in a moment

the story of the times

Homero Aridjis

Exaltation of Light

Aimé Mpane creates works of art that are solemn, poetic, fragile, visceral, and haunting all at once. There is great humanity present and a story being told. It is a story of greed, murder, terror, injustice, courage, and hope. Much of his work examines the relationships between Africa and the so-called civilized West after European powers convened for the Conference of Berlin in 1885. It was during this conference that Africa was divided into artificial territories for colonization and trade. King Leopold II of Belgium was given dominion over the Congo, a region 5 times the size of Belgium. Thus began a reign of terror that would see the Congo’s population decimated by approximately 10 million during Leopold’s État Indépendant du Congo, which consisted of forced labor, rape, mutilation and genocide. Though Leopold’s reign lasted only 23 years, its shadow lingers today as the region has faced decades of kleptocratic governments, multinational corporations and rebel militias with eyes focused on the extraction of wealth (diamonds, gold, cobalt, coltan, petroleum, and uranium) at any human cost. At present time “experts working in the Congo, and Congolese survivors, count over 10 million dead since war began in 1996 with the U.S.-backed invasion to overthrow Zaire’s (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) President Joseph Mobutu.”

Shadow and light have been intricate themes in Aimé’s work. A shadow is a region of darkness where light is blocked. There are cultures where the shadow is a flicker of life unable to end for some reason. Still others see the shadow as an ethereal presence around an object like a halo. Shadows can be the boogeymen who haunt our dreams and realities alike. The great shadow of capitalism has fully cast its shade upon the Democratic Republic of Congo. Your shadow is your own ghost, following you for all of your days. Making your way around the gallery space, take notice how your own shadow infiltrates certain installations, implicating you into their existence. In the giant shadow of night time Aimé paints portraits by firelight or candlelight in an energy-scarce city. To experience Aimé Mpane’s work is to journey in one man’s service to his people. Ultimately they are a way of keeping memories of events and people alive. They emerge from a dark history to become something beautiful; a requiem and sublimation.

Ryan Perry

Aimé Mpane was born 1968 into a family of artists in Kinshasa, Congo. He graduated in Sculpture from the Academie des Beaux-Arts, Kinshasa in 1990 and Ecole National Superieure des Arts Visuels de La Cambre, Bruxelles, Belgium in 2000, He presently teaches Sculpture at the Academie International d’Ete de Wallonie, Libramont, Belgium and as a Visiting Professor at the Academie des Beaux-Art in Kinshasa. Exhibitions include “DAK’ART” Bienniale de Dakar, Senegal, 2006,for which he was awarded the Jean Paul Blachére Foundation’s Critics Prize; Havana Biennial 2003; Africa for Africa, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Bruxelles, 2003; Musee de Katanga, Lubumbashi, Congo, 2002; Africa Sana, Quai Antoine Ier, Monaco 2001; and Centre Cultural Français, Kinshasa, 1991.

Aimé Mpane, “Couple Infernal (The Infernal Couple)”, 2004, Installation: mixed media, dimensions variable, 6’x14’x12’

Aimé Mpane, “Bach to Congo”, 2005, Installation: mixed media, dimensions variable 113”x90”x65”

Aimé Mpane, “Education (Inadequate Education)”, 2007, blackboard, wooden school chairs, variable dimension

(chalkboard)

The Code Noir (The Black Code)

We forbid any religion other than the Roman, Catholic, and Apostolic Faith from being practiced in public. We desire that offenders be punished as rebels disobedient of our orders…….

(postcard)

Rub harder, to become white! blanc!

– published by the Sisters of Charity

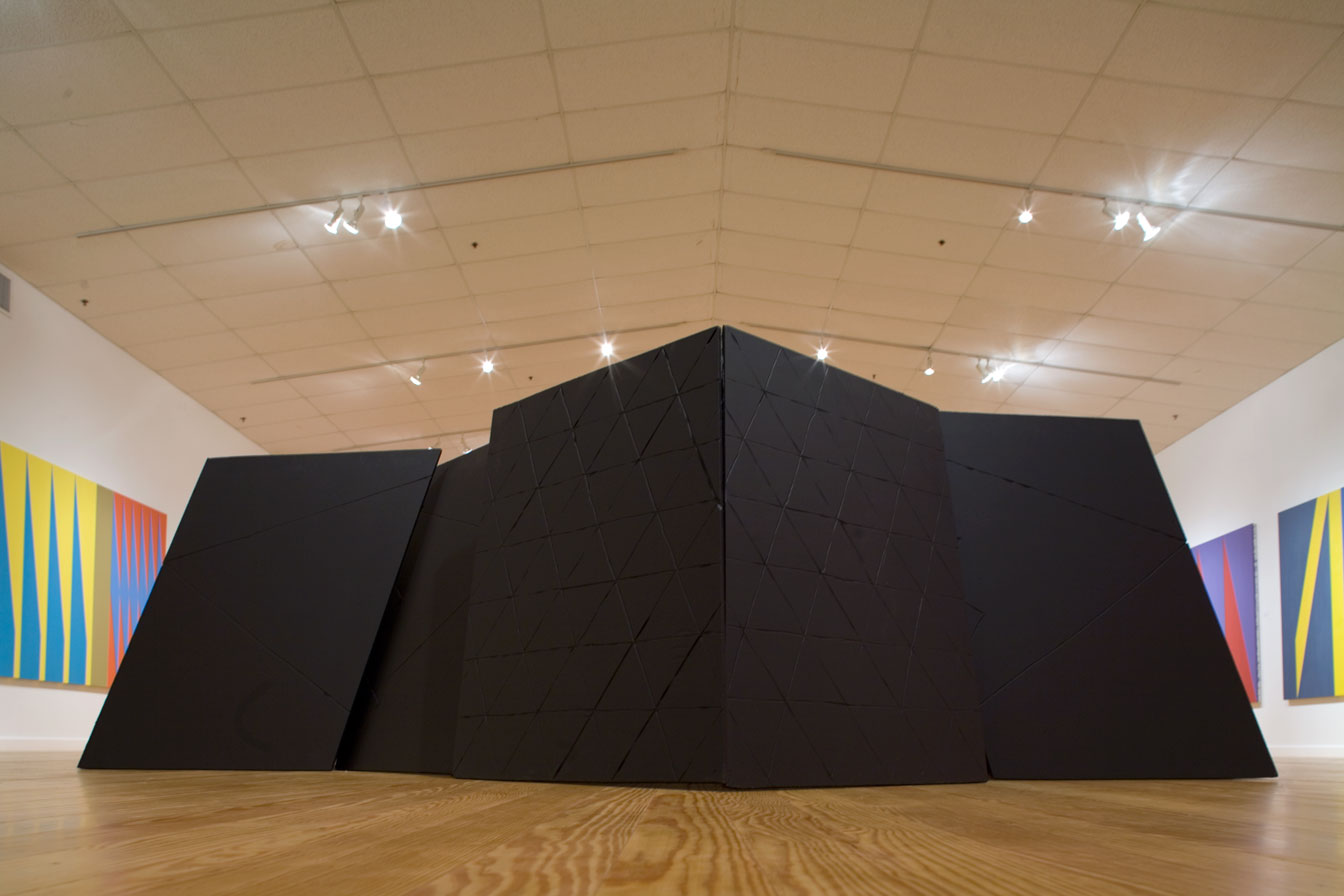

Installation view of James Little’s paintings and George Smith’s sculpture, Station Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007

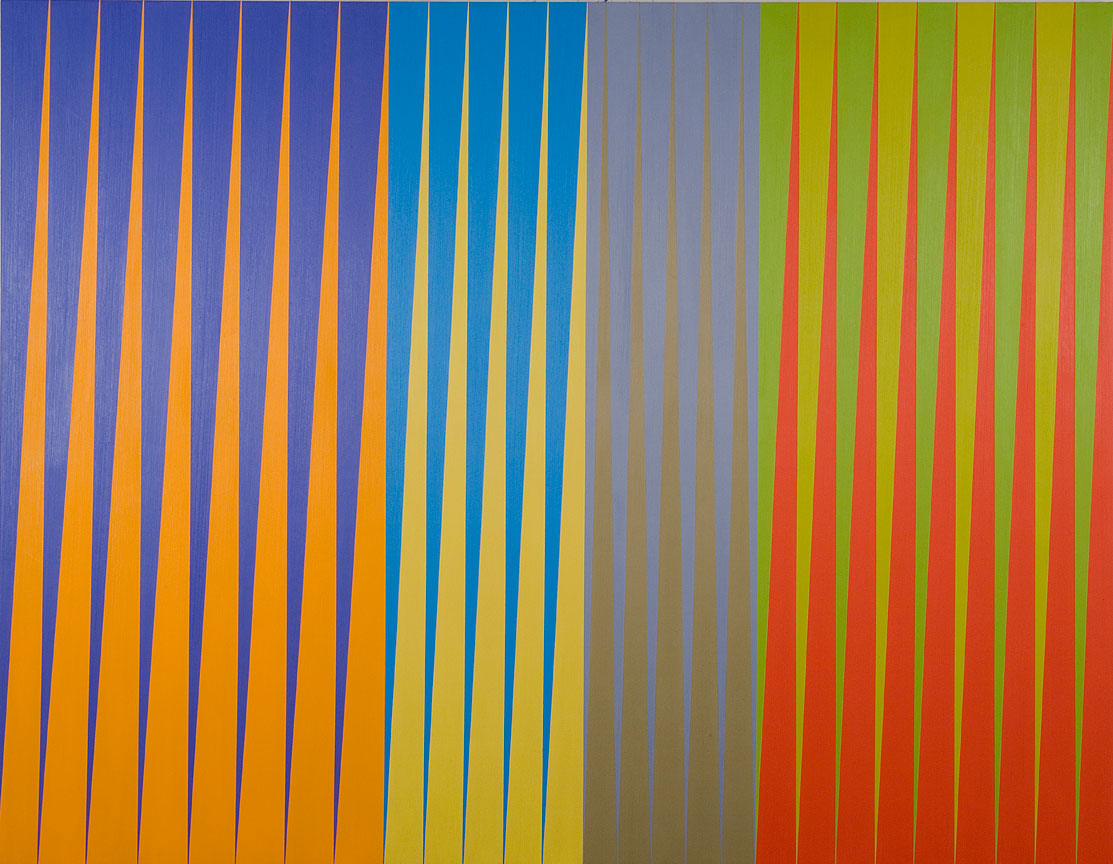

James Little, “Portrait of a Star”, 2002, oil, wax, canvas, 78”x96”

Great artistic skill, truthfulness, idealism, vision and passion are fundamental to the creation of a profoundly spiritual art. In this ravaged time of endless war, a fresh approach to the spiritual needs of the American people is critical to their mental health. Who can we turn to but artists and musicians who are free of the consumer orientation of contemporary culture and who are free of the nationalism that distorts the teachings of established religions. Exceptional artists who struggle to express their inner life and who endure the intense solitude of a spiritual quest are few in number, hard to find, and rarely celebrated. Nevertheless, they exist. James Little is one of them.

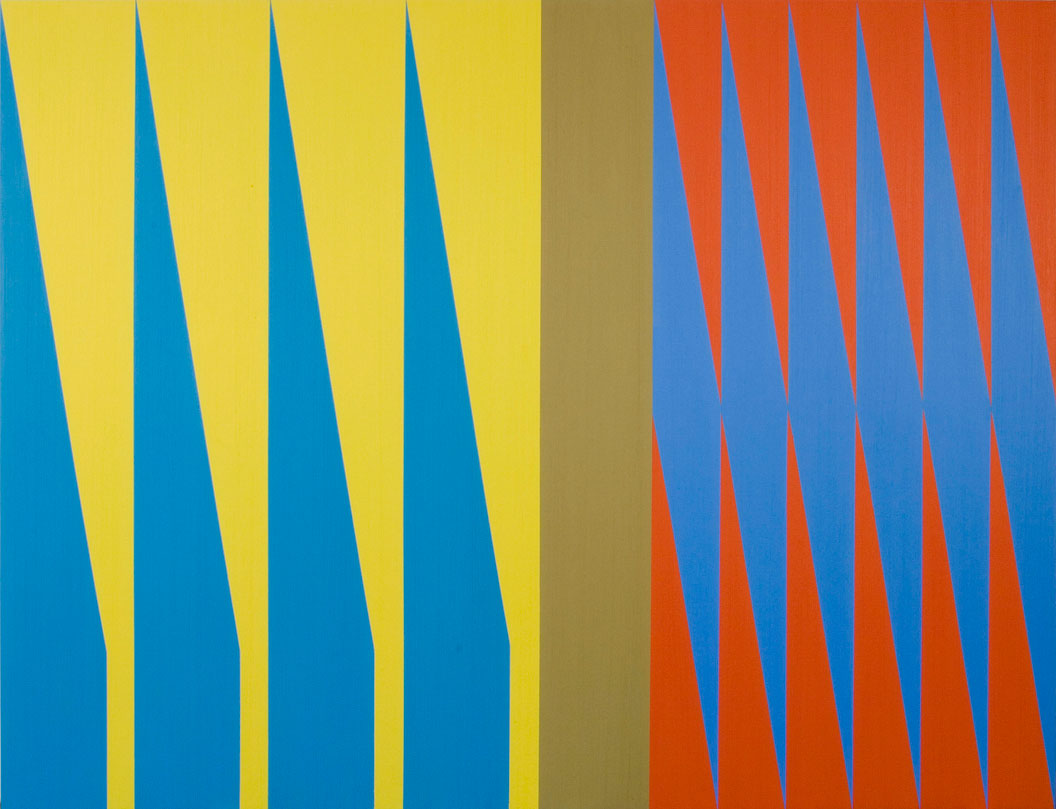

James Little’s paintings are original, sophisticated, and profound. They are expressionist and ceremonial in essence. They are quite distinct from earlier approaches to non-objective and hard edge painting. Little’s paintings use geometry and color in a way that reaches beyond their historical sources in Modern Art and go on to express a social and spiritual dynamic that is new to American art.

Earlier modern artists focused on the fundamentals of structure, color, and on the relationship between the pared-down, constituent elements of painting. However, the great artists of this persuasion were not purists, formalists, or devotees of art for art sake. They faced the critical issue of the spiritual versus the social content of their art. Mondrian’s neo-platonic paintings are the expression of his fervent idealism and mysticism. Malevich’s paintings are icons of revolutionary rebirth. Albers’ Aristotelian paintings reveal his color discoveries in the context of the unchanging, universal form of the square. Newman’s non-Euclidean paintings evoke the profoundly human drama of Jewish mysticism at the same time that they successfully challenge and go on to expand the Western tradition of painting.

Little has immersed himself in the same tradition of painting and enriched it and expanded it with a personal vision rooted in his African American and American Indian heritage. His paintings have soul — the power to ignite the spirit. Like the best Jazz, they express powerfully distilled emotions and take the art of painting to a level of intensity and conviction that is rare in contemporary American art. Little’s compositions are bold and supremely intelligent. With great simplicity, the artist creates a complex dynamic, using unique combinations of resonant colors and fundamental geometry. Triangular vectors move his color decisively up, down and across the canvas. There is an underlying rhythm and a reference to African design and to American Indian symbols as well as an abiding beauty, and the powerful impression or feeling that “something or someone” is fully on the move. Little’s paintings communicate the enduring spiritual power of his African American and American Indian heritage and occupy an important place in the history of modern American art.

James Harithas

James Little received his BFA at the Memphis College of Art and his MFA at Syracuse University in 1976. He has exhibited in museums and galleries in the United States and Europe.

James Little, “Bitter-Sweet Victory”, 2006, oil, wax, canvas, 76”x98”

James Little, “Einstein’s Axiom”, 2006, oil, wax, canvas, 76”x98”

James Little, “The Marriage of Western Civilization and Law of the Jungle”, 2007, oil, wax, canvas, 76”x98”

James Little, “Picasso’s Funeral”, 2006, oil, wax, canvas, 76”x98”

James Little, “Psychic”, 2007, oil, wax, canvas, 76”x98”

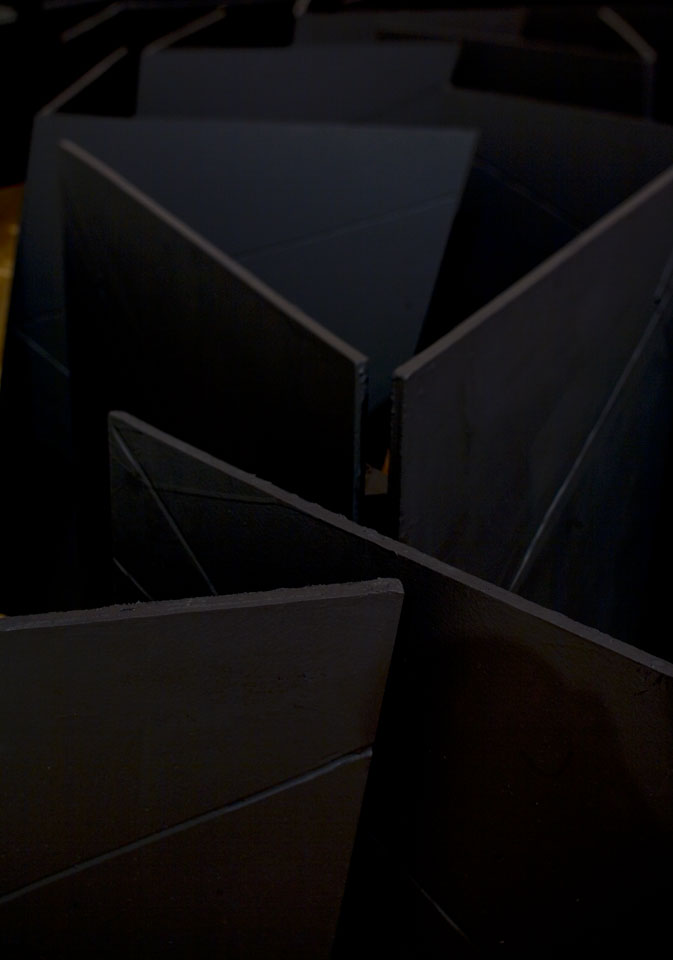

George Smith, “Return to Diankabou”, 2007, steel & enamel on wood, 3.5 x 12 2/3 x 22 1/12 ft. Consisting of 32 individual elements or parts, George Smith’s most recent work is a sculpture that is militarily both defensive and offensive. Each of the individual elements is shield-like and bears scarifications. Reflecting the strategic formations of the battlefield, the sculpture is a maze of vector-like movement that has no entrance, and thus conveys the unmanageable essence of war. The influence of Dogon art and architecture is evident in the geometry of the sculpture, but on another level, the work is a monument that bridges African-American spirituality and its African origins.

George Smith’s sculpture is powerful, original, and immensely dignified. On one level, it reflects his intellectual and aesthetic orientation and his skill and experience with steel construction. On another level, it communicates his spiritual ambition. Stylistically, his art is unique in that it synthesizes three fundamental sources: the sense of scale and the intuitive look of Abstract Expressionism, the flat-faced industrial geometry of Minimal Art, and the striations, expressive symbols and geometry inspired by the Dogon peoples of West Africa.

Minimal artists have been engaged in simplifying the vocabulary of form in sculpture through the use of industrial materials and clean geometric primary structures. The artists of this persuasion usually had their designs fabricated. Even though Smith’s sculpture was always hand-made, it expressed the structural clarity of the Minimal approach along with the baroque signature of Abstract Expressionism. Incidentally, the fact that his father was a worker in the steel mills in Buffalo, New York, may have been responsible for his choice of materials. However, it was to African art and architecture that Smith turned to find a geometry and spirituality which, unlike most contemporary American art, was not based on materialism. Younger artists like Smith who were well educated and had experienced the Civil Rights movement felt that they had earned the right to define themselves and their art through a mainstream international approach to form and content. Smith, in particular, enriched his sources and his previous approaches through his focus on Dogon art and architecture.

The Dogon, who hail from Mali in West Africa, have over the centuries developed a distinctive aesthetic and knowledge of astronomy that, along with their myths, are the unifying elements of their social and spiritual life. The Dogon believe that they came to earth from their original home on Sirius, the Dog Star, and consequently they orient their art and architecture to this star, resulting in a sense of scale and space that is almost limitless. In 1979, Smith went to Africa with the funds he received from the sale of a sculpture to Houston patron Dominique De Menil. There he studied the Dogon first hand and over the following years, he integrated their geometry into his sculpture. This caused his work to undergo a major change. His sculpture now communicated a profound sense of spirituality whose essence is ritual forms that evoke the unity of the tribe and, by extension, the unity of all things.

Early in the twentieth century, African art provided the dynamic and the juju that became central to the fundamental styles of Modernism. Fauvism, Cubism, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism were each in different ways vitalized by African art. By contrast, Pop Art and Minimal Art did not reference African Art. By going to the source tradition in Africa, Smith was able to rekindle this spirituality in his sculpture in a time of extreme darkness in the art world.

James Harithas

George Smith studied at the San Francisco Art Institute and Hunter College in New York City. He has exhibited widely throughout the United States. His recent exhibibitons on New York have been received with great acclaim. He is currently a professor of sculpture at Rice University.